Seventeen sets – ‘The Maids’ / ‘Deathwatch’, ‘Blood Wedding’, ‘Iron’, ‘Lemons, Lemons, Lemons, Lemons, Lemons’, ‘Love Letters’, ‘Speed-the-Plow’, ‘Hamlet’, ‘Kvetch’, ‘The Servant’, ‘Old Times’, ‘A Christmas Carol’, ‘Great Expectations’, ‘The Father’, ‘An Experiment With An Air Pump’, ‘The Heresy of Love’, ‘W.M.D. Woman of Mass Deception’

*

‘The Maids’ / ‘Deathwatch’

I’m a great believer in Minimalism – in the sense of ‘Less is More’ as well as ‘doing more with less’. In fringe theatre we simply don’t have the resources – time or money – of mainstream theatre, so we have to work more imaginatively.

Two flats, draped in silvery velvet material, gave a sense of luxury, and the gap between them served as the room’s window. Here, by moonlight, the sisters fantasize about being their mistress, for they envy her, and also plot to kill her with a cup of poisoned tea (seen in the foreground ).

During the interval, a hinged panel was swung round to fill the gap between the flats. As the second play started the prison Guard pulled down the drapes, revealing the prison walls beneath. The centre panel had become the cell door. He pulled the velvet cover off the huge bed to show the two hard prison beds below.

Moved round into an L shape, these became the sides of the cell, and defined the edges of the acting area. Genet’s point, it seems to me, is that the bourgeois Parisian apartment had really been a prison all along!

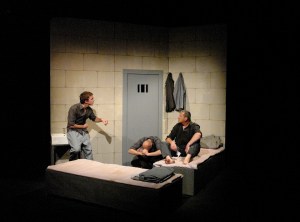

A really claustrophobic space, pooled in light in the middle of the stage, where the three actors moved round each other, jockeying for the position of ‘top dog’, for almost an hour.

*

‘Blood Wedding’

Federico Garcia Lorca’s play is about the drive to acquire and control land in the rural Spain of the 1930’s. A young woman has to marry a landowner’s son she doesn’t really love, to link two families’ estates – but at the wedding she runs off with her former admirer, for whom she feels real passion. Two families’ honour is outraged, and the couple are pursued into the forest. The action takes place in a number of different places, so my concept for the set was to have a very simple and stark arrangement of flats, painted off-white, which could be lit with different colours to suggest different locations.

This allowed for very smooth scene changes, without the need for elaborate set dressing. A chair was taken off, a table turned slightly, the lighting faded to a different colour – and there we were in a different house, or on an outside terrace, or in a church, or deep in the forest …

A key scene takes place on the outside terrace of the Bride’s house, and to suggest this location I constructed a canopy, complete with clinging foliage and flowers, which was lowered into position. In the scenes where it wasn’t used, the canopy was pulled out of eye-line back up into the lighting rig.

I like to incorporate some moving elements into my set designs where appropriate – it’s another way of getting our limited resources to work harder.

If you look carefully – you’ll see that on the background flats we used black paint to have the pale area sloping downwards towards the rear. This created the illusion of a much deeper set, in what was actually a fairly restricted space.

*

‘Iron’

Some sets can be constructed almost solely with light, and Rona Munro’s ‘Iron’ is one of those. It’s set in a women’s prison, and a large part of the action takes place in the visiting room, where there’s a table that Fay sits at with her daughter, constantly under the watchful eyes of the prison guards.

I wanted to give a sense of the warders walking backwards and forwards under the harsh prison lights, so I put a series of downlights to define their walkways. As the guards moved, they passed into hard pools of light, then on into darkness.

*

‘Lemons. Lemons, Lemons, Lemons, Lemons’

Lights, again. The set wasn’t my concept for ‘Lemons, Lemons, Lemons, Lemons, Lemons’ – but the director needed a constellation of lights above the actors, symbolising the words they spoke, which gradually extinguished as different scenes developed.

The action jumped back and forth in time, too, so I also had to light Judith Berrill’s torn-paper set in different colours, to signify the present or the past. Each hanging light had to wired separately so that we could control the arrangement as needed, I ended up using almost fifty metres of cable.

*

‘Love Letters’

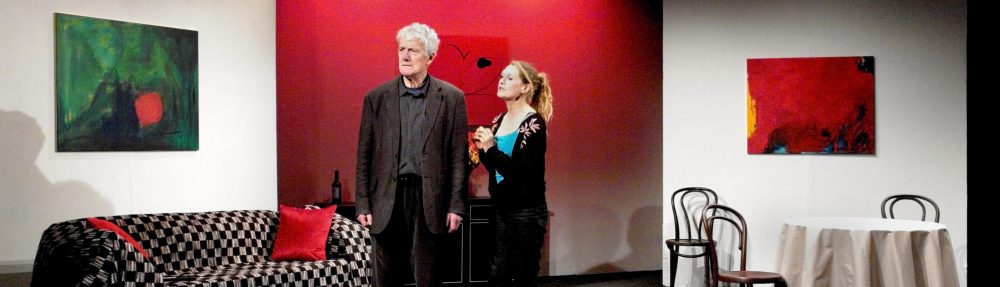

A R Gurney’s ‘Love Letters’ is an odd play, more like a rehearsed reading; as two actors usually sit side by side reading out an exchange of letters between two upper-class Americans. The correspondence spans almost forty years, and by the end the woman has died. Because it’s done by reading letters, it’s a popular production for celebrity actors, who can perform it with very little preparation.

When I came to direct the piece, I decided to put more meaning into Gurney’s words, by staging it as if the man has just come home from the woman’s funeral, and is re-reading their letters while reflecting on their lives. He read each of his letters to her as if remembering his feelings at the time, and then the woman, seated some way upstage, behind him, read her replies in the present tense, as if she was just writing them.

He was downstage in constant light, while she was left in darkness until her readings, when she was lit by a pool of softer, bluer light. The effect was that he was in the here-and-now, while she was a vision from his memory – or perhaps a ghost . . .

*

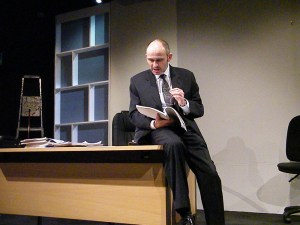

‘Speed-the-Plow’

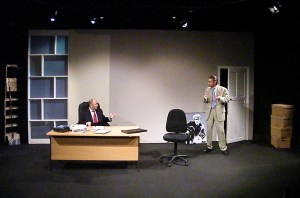

David Mamet’s ‘Speed-the-Plow’ is set in Hollywood, and the action moves between the office of a newly-appointed film producer, and his apartment at home.

That transition had to be carried out in front of the audience, so I designed a ‘glass wall’ for the office, that allowed us to see the secretary as she passed behind it. This was hinged so that it could be swung round to become the shelf unit in his apartment.

The script tells that his new office is being redecorated, so we put a patch of unfinished paint on the wall, and the stage crew were dressed in painters’ white overalls for the transition. I like to think that we turned a necessary scene change into a piece of theatre in its own right.

Opening the hinged panel also allowed passage of the desk and the sofa to and from their hiding place behind the set.

*

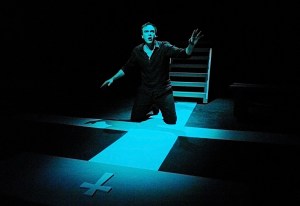

‘Hamlet’

I’ve designed a number of sets for Steven O’Shea’s productions – ‘Speed-the-Plow’ was also one of his.

O’Shea had written a cut-down version of Shakespeare’s play, eliminating all but the central characters of Hamlet’s immediate family.

We built a gantry, overlooking a central floor area defined by a painted cross leading to the tomb of Hamlet’s murdered father. We’ve used that well-built flight of steps in quite a few subsequent productions

I designed the lights so that small areas could be lit individually, increasing the sense of isolation of the protagonists.

*

‘Kvetch’

When Steven O’Shea came to direct ‘Kvetch’, he assured me that all Steven Berkoff’s play needed was a simple dining table, where the main character brings a colleague home.

He neglected to mention that the table had to be strong enough for four actors to stand on it – or that it had to be tall enough that they could change costumes underneath, for the bedroom scene – OR that I would have to construct dining chairs high enough to sit on while eating, and with integral steps to climb onto the surface.

I was ready to scream …

But I didn’t – and the result was worth it …

*

‘The Servant’

‘The Servant’ is a director’s nightmare – or creative opportunity. Robin Maugham’s play is about a man who inherits money and returns from Africa to live in London. His friends find him a house to rent, and a manservant to look after him. It’s a psychological piece, where the servant gradually becomes the dominant personality.

The action takes place in the house, with scenes alternating quickly from the lounge to the bedroom, on to the kitchen, then back to the lounge. And so on …

I designed a set consisting of a fixed flat with a door, and two lightweight double-sided flats that could be rotated to present the audience with a variety of combinations – a double bed for the bedroom scenes, for example, or a cooker (and the other flat set at an angle) to give us the kitchen scenes.

With different set configurations giving three different locations in the house, and lighting to produce a different time of day in each of them, there were many possibilities available to the director. The flats were quickly rotated as required and the action proceeded without delay, avoiding the need to drag on heavy props like the double bed and the cooker.

*

These aren’t my only set designs, of course.

Remember that you can see my rotating set for Pinter’s ‘Old Times’ in the January position on the ‘2014 Projects’ page.

The set panel gave us the living room on one side, with the bedroom on the reverse, and it was turned between Acts, during the interval.

The panel was also pivoted off-centre, so that it hid the bathroom door during Act one, and then revealed it for Act two.

As with ‘Speed-the-Plow’, which I mentioned above, the sofas, beds and table were all hidden behind the set during the Act when they were not needed.

*

*

‘A Christmas Carol’, which you can see more of on the 2015 page, has events which take place both inside rooms and outside in the street or, as spirits, on the night air.

I wanted to allow the action to flow seamlessly between locations, with an actor able to be inside a room looking out of the window, then give the audience a complete reversal of perspective by looking at the window from outside.

As part of the set, I made use of the column in the centre of the NVT upstairs stage to hang a window, which could be rotated by pushing it round as an actor looked through it. So we saw Scrooge’s back as he peered out through the panes, then as it was turned we saw him from the outside, with the scene he was looking at occupying the downstage area.

Left in either position, the window also acted as a basic set element, suggesting a wall and thus defining a room space.

*

I used the same technique on NVT’s 2019 production of ‘Great Expectations’. Here, the entire door frame rotated as the actors passed through from an exterior location to an interior setting.

*

There’s also ‘The Father’, which we did at NVT in 2019. Here the script required Andre’s flat to disappear by stages, which we achieved by blinding the audience with forward-facing lights while the stage crew removed various items from a blacked-out stage between scenes. The final scene takes place in some kind of nursing home – which may be where Andre’s been all along. I designed a hospital bed which we covered with a throw to transform it into a settee until the final reveal. None of the set changes took longer than twelve seconds.

*

*

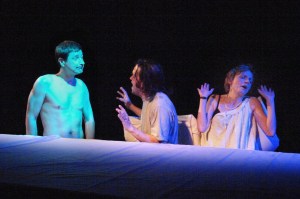

An Experiment With An Air Pump

As you will have seen by now – I hate clunky scene changes. Wherever possible I like the transitions to be seamless. When we came to do ‘An Experiment With An Air Pump’ we had to contend with a Newcastle house which was occupied by two different families, two centuries apart. The scenes jumped between 1799 and 1999. The eponymous play’s based on the painting by Joseph Wright of Derby, and the production started with a reproduction of the action on stage.

I decided to use a large black theatrical gauze as a central set element. Lit overhead from the front, it took on the appearance of a richly painted red wall – then when those lights were turned off and replaced with white light behind the gauze, the material simply disappeared, letting us see the eighteenth century interior of the house. The gauze also hid three musicians, who provided live accompaniment – you can see one of them behind the 18th century family.

Here’s the eighteenth century family’s maid, Isobel, in front of the house interior. She’s actually in front of the gauze, lit by the downstage lighting rig, while the light on the mantelpiece is behind the gauze. Which has disappeared ! Then reverse the process and we’re back in the twentieth century.

*

*

The Heresy of Love

‘The Heresy of Love’ was a huge project. Helen Edmundson’s play, about a seventeenth century Mexican nun, required several innovative solutions. The action occurs in various places – above is the Locutary, a room in the convent with a grille separating the visitors from the enclosed Sisters. I had to set narrow bands of light to define the barrier, which could then disappear when the location changed.

We had an arched window at the rear of the set, giving a view onto a range of back-projected images, ranging from the convent cloister and the Archbishop’s palace, to a nun’s cell – to locate the action in the foreground.

The stage didn’t provide enough space to project a big enough image on the window, so we bounced the image off a large mirror, thus doubling the projector throw length.

We were very pleased with the final effect.

*

*

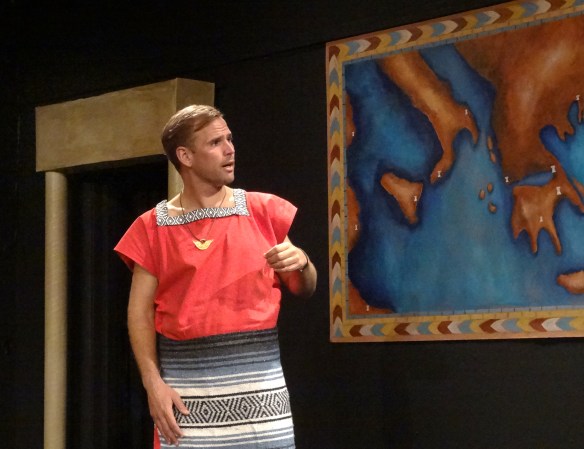

W.M.D. Woman of Mass Deception

We produced my play in NVT’s Studio space, as a simple black box set, with a minimum of cues to define the location: the Treasurer’s office in Agamemnon’s palace at Mycenae.

Just a doorway and a wall map of the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea, with daylight streaming through a ‘window’ in the corner, through which princess Iphigenia could glimpse the sea, past Argos.

The play was staged as the second half of a double-bill, along with ‘Sea Wall’, which had no set at all, other than a couple of black boxes. I found an elegant table to serve as the desk, which split into two to be hidden offstage during the first half. The black boxes were rearranged as a shelf to hold the Treasurer’s wine. You’ll know that I hate clunky scene changes, so we simply used the table as the House of Commons Dispatch Box for the last scene with Tony Blair in Parliament. Like all Prime ministers, he leans on it as he makes a statement to the House.

Just these few simple elements gave the audience all the visual cues they needed, with the cast entering through a portable doorway which was deployed for ‘W.M.D.’ in the interval, and Judith Berrill’s wonderful map (hidden by a black curtain during ‘Sea Wall’) acting as a guide for the geographic locations of the play, as well as rich decoration for the walls of Agamemnon’s palace.

*

*